From dead decks to living systems

A few weeks ago, I opened an old market-research deck. The slides were immaculate—fonts aligned, charts in perfect geometry, each page a monument to the effort behind it. I remembered the hours that go into such work: gathering fragments of data, stitching together surveys and interviews, nudging text boxes late into the night. And yet the insights were already fading. Whatever life they once carried was fixed in place, embalmed in PowerPoint, and filed away among a thousand other documents. The graphs depicted a world that no longer existed; the knowledge had become an artifact.

What is emerging now is something different: knowledge that does not expire at delivery, but continues to adapt as the world moves. In other words, knowledge that behaves less like a static object and more like a living system—replenishing itself, compounding in value, and requiring cultivation over time. Instead of one-off reports that freeze insights in time, we are moving toward dynamic “data gardens” of knowledge that grow and evolve continuously.

Lessons from a petrified forest

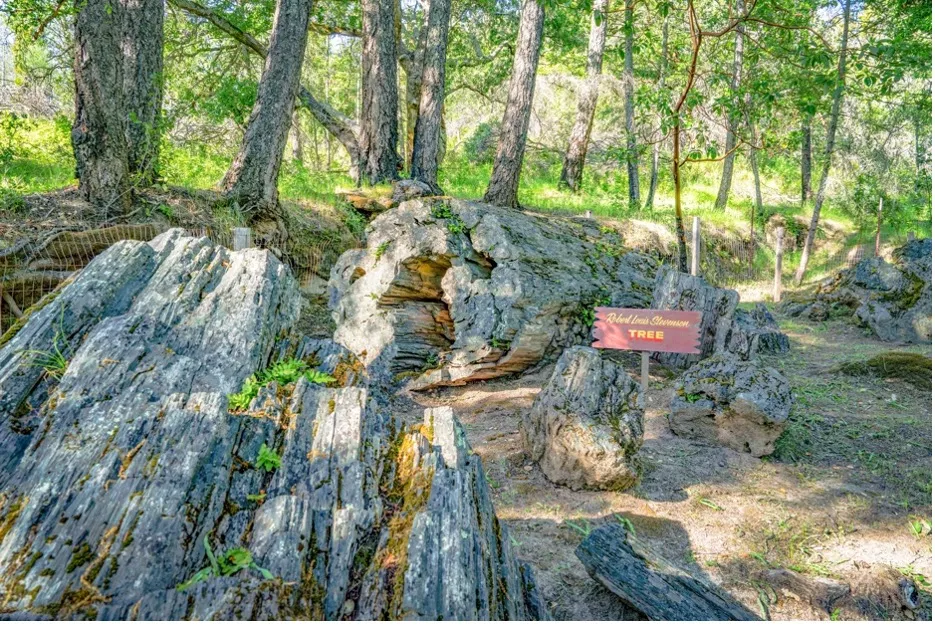

Once, a forest stood alive. Then a cataclysm buried it under ash and mud. Deprived of air, the wood did not rot; instead, mineral-rich water seeped through every cell. Over centuries, quartz replaced fiber, molecule by molecule, until the trees stood again—not as wood, but as stone. The grain and rings were still visible, but frozen forever. Strong to look at yet brittle underneath, the forest had become a monument.

And yet, even in a petrified forest, life returns. Lichens cling to the stone, etching nutrients from its surface. Mosses spread in shaded cracks, appearing brittle and brown until a rain revives them into green. Soil gathers in hollows, and in time, grasses and wildflowers push through. A juniper seedling may even root inside a fractured log, splitting the stone wider as it grows. Slowly, quietly, green reclaims the fossil. The petrified forest teaches several things at once: What looks permanent may be fragile; what looks fragile may endure. Time moves at different scales—stone takes millennia to form, but moss springs back overnight. And the past does not vanish: fossils and flowers coexist, the mineral skeleton of history serving as a foundation for renewal.

These lessons form a powerful analogy for business knowledge. Our decks, reports, and PDFs are like petrified wood—precisely preserved but inert. Left alone, they cannot adapt. Yet given the right conditions—fresh data, interpretive tools, human insight—even fossilized knowledge can host new growth. The task is not to discard the past, but to treat it as soil: a substrate where living systems can take root, adapt, and evolve. In the same way that lichens and moss can rejuvenate a petrified log, new data and analysis can rejuvenate old insights, extracting nutrients from them and putting them in context for the present.

How business knowledge becomes petrified

For decades, business knowledge has been treated less like a living thing and more like a deliverable. Consultants write reports, agencies build slide decks, internal teams produce PDFs. The ritual never changes: circulate the document, present the findings, lock in the plan, then tuck it neatly into the archive. This approach worked—at least it appeared to—in an era of quarterly reviews and annual budgets. The cadence was slower, the world moved less violently, and everyone could pretend that the artifact on the table represented enduring truth. But that pretense baked in fragility. One surprise in the market and the carefully laminated consensus would shatter. Leaders thought they were steering from evidence; in reality, they were steering from fossils.

This is the paradox of the old paradigm: what passed for “data-driven” was really “data-once.” Business knowledge died the moment it was published, embalmed in the artifact itself. As philosopher Karl Popper warned, the instant you treat knowledge as final, you step out of the game of learning. In science, truth is never absolute or permanent – all knowledge remains provisional, conjectural, and open to revision. A report that claims to be conclusive isn’t insight at all; it is dogma, delivered in bullet points. The old paradigm of business knowledge had a good run, but the cause of death is clear: false permanence. The world moved on, but the knowledge did not move with it.

Lichen on petrified wood in Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park. Even fossilized remains can host new life under the right conditions.

The data garden: Growing living insights

Reports may expire, but knowledge doesn’t have to. With today’s tools—ranging from advanced language models to real-time behavioral data streams—we can begin to build living insight systems. These are knowledge systems that do not stop at delivery, but continue to learn and update as the world shifts. Living knowledge behaves less like a static report and more like a learning organism:

- Adaptive to new signals: It updates with incoming data, adjusting conclusions when the facts change. Instead of a snapshot, it’s a live feed. Trends are tracked as they form, not just after the fact.

- Accumulative memory: It retains historical knowledge and continuously integrates new findings. Each piece of analysis layers on the previous, creating an additive, compounding knowledge base rather than scattered one-off studies.

- Patterns across time: It can surface patterns and anomalies that only become visible through continuous observation across different time scales. You can zoom from the “canopy” (big picture trends) down to the “leaf” (individual data points or anecdotes), all within one evolving framework.

- Forward-looking foresight: As rhythms and correlations emerge, a living system can project patterns forward, offering a glimpse of where things are headed (with appropriate probabilities or confidence bands). Decisions become not just about where we are, but where we are likely going.

In a traditional model, each research project is a closed loop—formulate question, gather data, produce insight, then stop. In contrast, a living insight system is an open-ended loop. It can be interrogated again and again with new questions. Every interaction with it—every question asked, every correction or feedback given, every annotation added—becomes part of the system’s intelligence. In effect, knowledge becomes a flywheel that gets smarter with use. This is not just a speed upgrade; it’s a fundamental redefinition of what a business decision is. Decisions are no longer bets placed on a frozen snapshot; they become acts of navigation inside a shifting, living landscape.

Crucially, all these growing insights rest on a singular foundation – a unified source of truth that evolves, rather than a dozen disconnected spreadsheets and slide decks. By cultivating a single “data garden,” organizations ensure that insights compound in one place. The system becomes richer over time, instead of obsoleting itself every quarter. The result is a compounding competitive advantage: much like companies that harness real-time analytics outperform those stuck in retrospective analysis, companies that cultivate living knowledge will outmaneuver those paging through last quarter’s static report.

Context is the soil: Why insight need meaning

Even living systems can falter if they lose their roots. Strip away context, and what looks like insight quickly shrivels into noise. Data by itself, no matter how real-time or abundant, can mislead without human interpretation and cultural understanding. This is where anthropology and qualitative context enter the picture, enriching the data garden like nutrients in soil.

Consider a classic example from the 1990s: Intel’s market research data initially suggested that home computers lived mostly in home offices (essentially treating PCs as work tools). But when Intel sent anthropologists into real households, they discovered a different reality—families were keeping the PC in communal spaces like the kitchen, using it as a hub for homework, recipes, and family activities. This cultural insight reframed the personal computer not as an office machine, but as a family communication and entertainment hub. In fact, Intel’s early ethnographic studies revealed so much untapped potential in home use that the company created an entire division for home computing platforms. The data (sales figures, usage stats) only told part of the story; ethnography uncovered the meaning behind the data.

This example underscores the danger of models without meaning. Dashboards might show a metric moving—say, loyalty scores dipping or customer churn rising—but they can miss why it’s happening. Is that churn just random loss, or is it part of a larger cultural shift (for example, late-night snacking moving from diners to delivery apps)? Anthropology and other human-centric research provide the texture and narrative behind the numbers. They reveal that what might look like a drop in usage is actually a change in ritual or behavior. In short, they restore meaning to the metrics.

A model that only counts signals is like a plant fed on artificial sunlight: it might look healthy for a while, but eventually it collapses because it lacks real nutrients. In contrast, a model that interprets rituals, motives, and cultural logics can truly thrive and persist. Context acts as the soil that anchors your living knowledge system, ensuring it stays relevant and robust. Crowd-sourced forecasts and behavioral models, when grounded in real-world context, encourage more objective and adaptive assessments of a situation, preventing decision-makers from jumping to the wrong conclusions. In a living data garden, quantitative signals and qualitative insights work together symbiotically—just like the fungi and algae in lichen—each enabling the other to survive and grow.

How living knowledge changes decision-making

Living knowledge doesn’t just change what leaders see; it changes how they feel and act when making decisions. When knowledge was frozen and fragmentary, leaders often craved the comfort of closure—the illusion of certainty from a report stamped “Answer: Final.” But that closure is fragile and short-lived. In a living insight paradigm, closure is replaced by continuous engagement. Decisions feel less like definitive verdicts and more like ongoing adjustments, like steering a ship through changing weather.

Here are some concrete ways that embracing living knowledge will transform how you work:

- Compressed strategy cycles: What once took a quarter to study and validate might now take a week. With an always-on insight system, waiting for the next annual report or quarterly review will feel as antiquated as waiting for the mail. Organizations can sense and respond faster.

- Earlier detection of risks and opportunities: Weak signals are picked up before they harden into full-blown crises or missed opportunities. A subtle shift in customer sentiment or a niche competitor’s experiment can be spotted and evaluated in near real-time, not discovered when it’s too late. Research indicates that companies able to consume and act on real-time intelligence gain a decisive edge, effectively separating industry winners from losers.

- Every interaction trains the system: As mentioned, every question asked of the system, every correction or input from an analyst, becomes new data. This means your knowledge base is literally learning from your team’s collective intelligence. Over time, the organization’s knowledge capital compounds. Just as modern AI systems improve via continuous feedback loops, your business intelligence grows sharper with each use—creating a virtuous cycle or data “flywheel” of improvement.

- Decisions gain foresight, not just hindsight: Traditional reports are retrospective—they tell you what happened last month or last year. Living models, by contrast, are also forward-looking. They not only describe what is happening now, but, based on pattern recognition and scenario modeling, they sketch what is likely next (complete with confidence ranges that you can probe and challenge). Leaders start asking “Where are we going, and why?” rather than only “What did we do, and why?”

- Shifting competitive advantage: The advantage in business intelligence shifts from those who simply hoard the most data or produce the thickest reports to those who can navigate a living system deftly and interpret it through a human lens. In the past, having a big archive or a proprietary dataset was the moat. In the future, the moat is the ability to rapidly learn and adapt—much like agility in using real-time analytics is now a bigger advantage than sheer data volume. Those who fail to adapt will find themselves paging through last quarter’s static deck while the market has already moved on.

In essence, leadership in a living knowledge environment feels more like piloting and less like judging. It’s a shift in mindset from seeking certainty to embracing adaptability. Decision-makers become more comfortable with continuous hypothesis-testing and refinement, rather than clinging to a single version of “the truth.” This can energize an organization: when everyone knows that insights will update and that their input can influence the system, people tend to stay more engaged with the data rather than filing it away.

Toward a cultivation culture

For centuries, our approach to business knowledge has been to embalm it—to freeze insights in slides, entomb them in PDFs, or bury them in databases and SharePoint folders. Like a forest turned to stone, our knowledge stores have been preserved in detail but left incapable of growth. They often appear strong and comprehensive, but under stress they prove brittle and quickly outdated.

For the first time, technology affords us the chance to let our knowledge live. But simply having the technology is not enough; we must also design our workflows and culture for adaptation. In this new paradigm, a decision isn’t a one-time decree—it’s part of an ongoing training process that shapes the intelligence you will use tomorrow. Knowledge compounds, foresight grows, and your organization becomes smarter and more resilient over time.

The petrified forest reminds us that what looks permanent may actually be fragile, and what looks tentative or fragile may be what endures. It shows that the past never completely disappears: fossils and flowers can coexist, with the old providing a foundation for the new. And it teaches that renewal depends on conditions - rain, soil, pioneer species—preparing the ground for life. In business, the “rain” is fresh data and human insights; the “soil” is context and culture; the pioneer species are those initial projects and champions that prove the concept. Leaders aiming to foster living knowledge must create the conditions where insight refuses to stay buried. This means investing in systems that integrate data continuously, encouraging cross-functional teams to update and challenge assumptions frequently, and valuing learning over simply being right. It also means letting go of the museum mentality—stop curating a pristine archive of past reports, and start cultivating a garden of current insights.

The future belongs to the green shoots that can split stone—to the organizations that nurture systems capable of learning, evolving, and staying human-centric in their interpretation. Those who embrace this living insight approach will navigate uncertainty with agility and creativity. In contrast, those who cling to fossilized knowledge will find their strategies cracking under the pressure of a changing world.